Shoulder pain can derail your fitness goals. That sharp twinge during a lift is a frustrating signal to stop. However, you do not have to abandon your workout routine entirely. Smart modifications can keep you active while protecting your joints. Understanding which exercises to avoid is the first critical step. Subsequently, learning safer and equally effective alternatives will empower you to train with confidence. This guide will help you navigate the gym, protect your shoulders, and continue building strength without pain.

A quality resistance bands set shoulder exercise provides versatile strength training options for home workouts, allowing you to target multiple muscle groups effectively. Additionally, a shoulder pulley system over door helps improve range of motion and flexibility, making it ideal for shoulder rehabilitation and recovery. You’ll also find that a quality shoulder wand stretching bar collapsible is an essential fitness accessory that enhances your workout routine and supports your fitness goals. Don’t forget that a door anchor resistance band exercise creates stable anchor points for resistance band exercises, expanding your workout possibilities at home. You’ll also appreciate that a set of adjustable dumbbells set weights provides versatile weight training options without taking up much space, perfect for home gyms. To complete your setup, a quality exercise ball stability ball 55cm is an essential fitness accessory that enhances your workout routine and supports your fitness goals. For best results, a shoulder therapy kit rehabilitation helps improve range of motion and flexibility, making it ideal for shoulder rehabilitation and recovery. Another great option is heating pad microwave shoulder wrap. Additionally, a reusable ice pack gel reusable shoulder helps reduce inflammation and soreness after workouts, promoting faster recovery. You’ll also find that a thick yoga mat thick non slip exercise provides cushioning and support for floor exercises, protecting your joints during workouts. Don’t forget that a quality massage gun percussion therapy is an essential fitness accessory that enhances your workout routine and supports your fitness goals. You’ll also appreciate that a quality posture corrector brace back support is an essential fitness accessory that enhances your workout routine and supports your fitness goals. Finally, a resistance band door anchor handles creates stable anchor points for resistance band exercises, expanding your workout possibilities at home.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Why Your Shoulders Are So Vulnerable

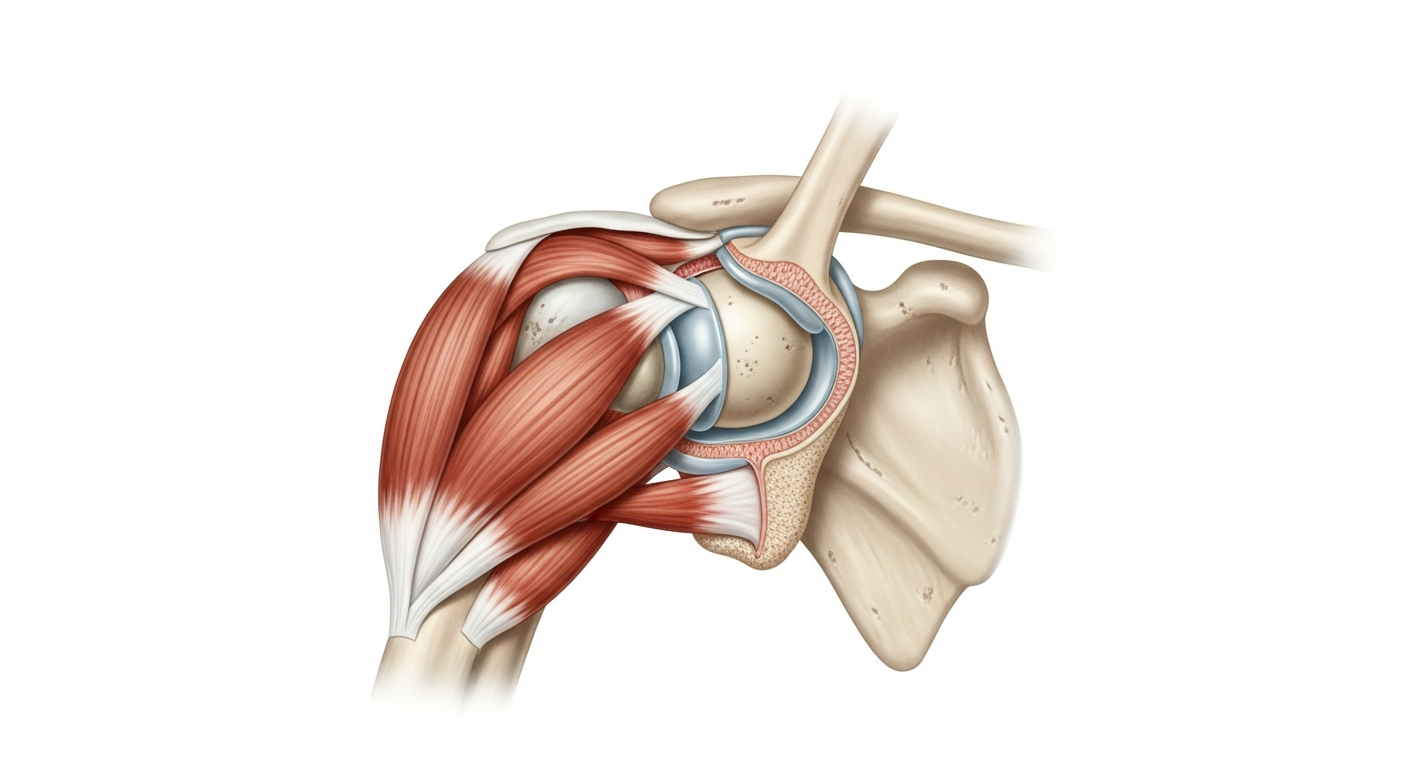

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body. Source This incredible range of motion, however, comes at a cost: instability. The joint, a ball-and-socket structure, relies on a complex network of muscles and tendons called the rotator cuff to stay stable. These tissues work hard to control movement and keep the head of the humerus (the upper arm bone) centered in its socket.

Many common gym exercises can place these delicate structures under immense stress. When the rotator cuff tendons get pinched between the bones of the shoulder, it causes a painful condition called impingement. Over time, this can lead to inflammation, fraying, and even tears. Therefore, choosing exercises that respect your shoulder’s natural mechanics is crucial for long-term health and progress.

4 Common Exercises That Can Worsen Shoulder Pain

Certain popular movements are frequent culprits behind shoulder discomfort. While some people can perform them without issue, they pose a higher risk for those with existing pain or poor mechanics. Here are four exercises you should consider modifying or replacing.

1. The Overhead Press (Barbell Military Press)

The classic barbell overhead press requires significant shoulder mobility. Pressing a bar directly overhead can narrow the space where your rotator cuff tendons pass. If you lack the necessary flexibility, this movement can directly compress those tendons, leading to impingement. The fixed position of the barbell also forces your shoulders into a potentially unnatural path, adding further stress.

2. Upright Rows

Upright rows put the shoulder in a position of extreme internal rotation while under load. This motion is a well-known mechanism for causing shoulder impingement. As you lift the weight toward your chin, you dramatically reduce the space within the shoulder joint. This action effectively pinches the tendons and bursa, creating friction and inflammation. For this reason, many physical therapists and coaches advise against this exercise entirely.

3. Dips

While the dip is undeniably effective for building powerful triceps brachii and contributing to pectoralis major development, its unique movement pattern can indeed place significant and sometimes detrimental stress on the delicate structures of the glenohumeral joint (the main shoulder joint). Understanding these mechanics is crucial for injury prevention, especially for those with pre-existing shoulder concerns.

Here’s a deeper look into why dips can be problematic and how to approach them safely:

The Mechanics of Shoulder Stress During Dips

The primary concern with dips centers around the anterior shoulder capsule and the structures that stabilize the front of the joint.

- Excessive Humeral Head Glide: As you descend in a dip, particularly when going deep (shoulders dropping significantly below the elbows), the humeral head (the ball of your upper arm bone) tends to translate forward and slightly inferiorly within the glenoid fossa (the socket). This excessive forward movement, known as anterior humeral head glide, stretches the anterior glenohumeral ligaments and the anterior joint capsule. Over time, this can lead to capsular laxity or even instability.

- Biceps Tendon Aggravation: The long head of the biceps tendon runs through a groove at the front of the humerus (the bicipital groove) and attaches inside the shoulder joint. When the humeral head glides excessively forward and rotates internally, it can compress, shear, or friction against this tendon. For individuals with existing biceps tendinopathy or SLAP tears (a tear in the labrum where the biceps tendon attaches), this action can be acutely painful and worsen the condition.

- Compromised Scapular Stability: Effective shoulder function relies heavily on the scapula (shoulder blade) moving correctly on the rib cage. In a dip, the scapula should ideally depress (move down) and retract (move back) to provide a stable base for the humerus. However, if an individual lacks adequate scapular control or strength in muscles like the lower trapezius and rhomboids, the scapula can protract (round forward) and elevate, further exacerbating the forward roll of the shoulders and increasing stress on the anterior capsule.

- Internal Rotation Bias: As the shoulders roll forward, the humerus tends to internally rotate. This position can place additional strain on the rotator cuff muscles, particularly the subscapularis (an internal rotator) and can create an unfavorable environment for the other rotator cuff muscles (like the supraspinatus) which are crucial for dynamic stability.

Key Risk Factors and Poor Form Indicators

Several factors amplify the risk of shoulder injury during dips:

- Excessive Depth: Allowing your shoulders to drop significantly below your elbows, or extending the range of motion past approximately 90 degrees at the elbow, dramatically increases the anterior stress on the shoulder joint. The deeper you go, the greater the stretch on the anterior capsule and ligaments.

- Over-Leaning Forward: While a slight forward lean can shift emphasis towards the chest, an excessive forward lean further encourages the shoulders to roll forward and the humeral head to translate anteriorly, intensifying the stress.

- Lack of Scapular Control: Failing to actively depress and retract your shoulder blades throughout the movement means you’re not properly stabilizing the shoulder girdle. This often manifests as a “shrugging” motion or allowing the shoulders to round excessively.

- Pre-existing Conditions: Individuals with a history of:

- Anterior shoulder instability

- Shoulder impingement syndrome

- Biceps tendinopathy

- Rotator cuff tears or tendinitis

- AC joint issues

are at a much higher risk of aggravating their condition with dips.

Practical & Actionable Advice for Shoulder Health

If you experience shoulder pain during dips, or if you have a history of shoulder issues, consider these strategies:

- Prioritize Pain-Free Movement: The most critical rule is to avoid any exercise that causes sharp or increasing pain. Persistent pain is a signal that something is wrong.

- Modify Your Dip Technique (If Pain-Free):

- Limit Depth: Do not allow your shoulders to drop below your elbows. Aim for roughly 90 degrees at the elbow joint, or even slightly less if that feels better.

- Maintain Scapular Stability: Actively depress and retract your shoulder blades. Think “chest proud” and “shoulders back and down” throughout the movement. Avoid letting your shoulders shrug up towards your ears.

- Control the Eccentric Phase: Lower yourself slowly and with control. Avoid bouncing at the bottom.

- Body Position: Keep your torso relatively upright. A slight forward lean is acceptable for chest emphasis, but avoid excessive leaning.

- Consider Regressions and Alternatives:

- Assisted Dips: Use an assisted dip machine or resistance bands looped over the dip bars to reduce your body weight and allow for better control and form.

- Bench Dips (Modified): Perform dips with your hands on a stable bench behind you. To reduce difficulty and shoulder stress, keep your feet on the floor with knees bent. For more challenge, extend your legs or elevate your feet. Even with bench dips, be mindful of depth and shoulder position.

- Targeted Strength Alternatives:

- For Triceps:

- Overhead Dumbbell Extensions: Focus on maintaining a stable shoulder position.

- Triceps Pushdowns (Rope or Bar): Excellent for isolating the triceps with minimal shoulder stress.

- Close-Grip Bench Press: Can be a good alternative if shoulder stability is maintained.

- Skullcrushers (Lying Triceps Extensions): Perform with a slight elbow bend at the bottom to protect the joint.

- For Chest:

- Dumbbell Bench Press (Flat or Incline): Allows for a more natural range of motion and easier modification of depth and hand position compared to a barbell.

- Push-Ups: Highly versatile, can be modified with incline (easier) or decline (harder) variations. Focus on maintaining a strong plank position and scapular control.

- Cable Flyes: Provides constant tension and allows for a customizable range of motion.

- Strengthen Supporting Muscles: Incorporate exercises that improve scapular stability and rotator cuff strength. Examples include:

- Face Pulls

- Band Pull-Aparts

- Y-T-W-L Raises

- Scapular Push-Ups (focus on protraction/retraction)

By understanding the biomechanics and implementing these strategies, you can either perform dips more safely or choose effective alternatives that support your fitness goals while protecting your shoulder health. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional or certified strength coach if you have persistent shoulder pain or concerns.

4. Behind-the-Neck Pulldowns or Presses

Any exercise that involves pulling or pressing a bar behind your neck is a major red flag for shoulder health. This movement forces your shoulders into an extreme range of external rotation. It places the rotator cuff and the ligaments at the front of the shoulder under excessive tension. This position offers no significant muscle-building advantage over front-facing variations. In contrast, it dramatically increases the risk of dislocation and rotator cuff injury.

Safer and Smarter Alternatives for a Pain-Free Workout

Avoiding risky exercises does not mean you have to stop training your shoulders or upper body. In fact, many alternatives are not only safer but can also be more effective for targeting specific muscles. These movements promote better shoulder mechanics and build stability.

Instead of Overhead Press, Try the Landmine Press

The Landmine Press is a fantastic alternative. By pressing the bar upwards and forwards at an angle, you avoid direct overhead compression. This path of motion is much more natural for the shoulder joint. It still effectively targets the deltoids and triceps without pinching the rotator cuff. Furthermore, it engages your core for added stability, making it a powerful full-body movement.

Instead of Upright Rows, Try Dumbbell Lateral Raises

Advanced Medial Deltoid Development Strategies

The medial deltoid serves as the primary architect of shoulder width, creating that coveted V-taper silhouette when properly developed. Understanding the biomechanics behind effective lateral deltoid training requires examining the muscle’s anatomical function and optimal recruitment patterns.

Perfecting the Dumbbell Lateral Raise Technique

The “pouring water” cue represents a crucial biomechanical principle that addresses external rotation positioning. This thumb-up orientation accomplishes several key objectives:

- Maintains optimal humeral head positioning within the glenoid fossa

- Reduces subacromial impingement risk by creating more space under the acromion

- Maximizes medial deltoid fiber recruitment while minimizing anterior deltoid compensation

- Prevents internal rotation stress that commonly leads to rotator cuff irritation

Progressive Loading Parameters:

- Beginner Phase: 8-12 reps with 2-3 second controlled lowering (eccentric)

- Intermediate Phase: Add pause reps (2-second hold at top) or tempo variations

- Advanced Phase: Incorporate mechanical drop sets or partial range extensions

Scaption Raise: The Anatomically Superior Alternative

Scaption raises align with the scapular plane, which sits approximately 30-40 degrees anterior to the frontal plane. This positioning offers distinct advantages:

Biomechanical Benefits:

- Reduces capsular stress by following the shoulder’s natural movement arc

- Optimizes length-tension relationships in the deltoid muscle fibers

- Minimizes impingement potential compared to pure frontal plane movements

- Enhances functional carryover to real-world movement patterns

Execution Protocol:

- Position feet shoulder-width apart with slight forward lean

- Initiate movement by lifting elbows first, maintaining 15-20 degree elbow flexion

- Control the ascent to shoulder height over 2-3 seconds

- Emphasize the eccentric phase with 3-4 second lowering tempo

Complementary Medial Deltoid Exercises

Cable Lateral Raises: Provide constant tension throughout the range of motion, particularly beneficial during the bottom portion where dumbbells offer minimal resistance.

Machine Lateral Raises: Allow for heavier loading while maintaining strict form, ideal for strength-focused phases or when fatigue limits stabilization.

Upright Rows (Modified): Using a wider grip and limiting range to chest height can effectively target medial delts while avoiding shoulder impingement.

Programming Considerations for Shoulder Health

Volume Distribution:

- 2-3 exercises targeting medial deltoids per session

- 12-20 total sets per week for intermediate trainees

- 48-72 hour recovery between intensive shoulder sessions

Injury Prevention Protocols:

- Always perform dynamic warm-up including arm circles and band pull-aparts

- Incorporate posterior deltoid strengthening to maintain shoulder balance

- Monitor for any anterior shoulder discomfort and adjust angles accordingly

Instead of Dips, Try Close-Grip Push-ups or a Neutral-Grip Dumbbell Press

For a safer pressing movement, push-ups are an excellent choice. They are a closed-chain exercise, which tends to be friendlier to joints. A slightly narrower hand position will emphasize the triceps and chest without over-stretching the front of the shoulder. Another great option is the Dumbbell Bench Press with a neutral (palms facing each other) grip. This grip allows your shoulders to move more freely and naturally compared to a fixed barbell.

Instead of Behind-the-Neck Movements, Stick to the Front

The fix here is simple and effective. Perform your lat pulldowns and presses to the front of your body. Pulling the bar down to your upper chest is the standard, safe, and proven way to build a strong back. It effectively engages your latissimus dorsi muscles without putting your shoulder joints in a compromised position. There is no need to take unnecessary risks with behind-the-neck variations.

Conclusion: Train Smart for Long-Term Health

Experiencing shoulder pain does not mean your days of lifting are over. It is simply a signal from your body to be more mindful of your exercise selection and form. By swapping high-risk movements for smarter, safer alternatives, you can continue to build strength and muscle. Always prioritize a thorough warm-up and listen to your body’s feedback. Ultimately, consistency and joint health are the true keys to achieving your long-term fitness goals.